Rainwater Harvesting and Recycling in the Galapagos Islands

Fresh water is a scarce commodity in the Galapagos.

That fresh water is scarce on a volcanic island will come as no surprise. Native and endemic species have evolved in ingenious (and sometimes distasteful!) manners to adapt themselves to food and water shortages (even more so now with climate change). Yet, human demands put constant pressure on this life-sustaining resource. Historically, the earliest settlers in the 19th century had difficulty finding steady supplies of freshwater, barely surviving to tell the tale. San Cristobal is one of the archipelago’s only islands to contain a visible and accessible source.

“There is no lack of water in the Mojave Desert unless you try to establish a city where no city should be.”- Edward Abbey (American author and environmentalist).

Fresh water sources in the Galapagos

Founders, Michael Mesdag and Stephanie Bonham-Carter raised their two children at Galapagos Safari Camp.

At the time of designing the camp, and still to this day, the primary water source for most residents on Santa Cruz island (including numerous hotels and guesthouses) comes from the main port town of Puerto Ayora, where it is extracted from basal aquifers. Not only does it have to be transported by truck (thereby increasing its carbon footprint), but it is also expensive and of poor quality (brackish, slightly salty, and at greater risk of contamination due to the incautious disposal of sewage waste in the port town.

From the onset, Michael and Stephanie felt passionately about balancing their guests’ expectations with the responsibilities of looking after, and working in harmony with the swath of wilderness they felt so fortunate to call their home. Transporting water across the island by a fleet of trucks on a daily or even weekly basis, wasn’t an option for them. They were determined to find a better, more sustainable solution.

Finding a sustainable water collection solution

Sustainable water cycle management is crucial on the Galapagos Islands

The obvious answer was to build a reservoir to collect rainwater. What was less obvious was finding an affordable way of keeping a reservoir free from algae, insects, and other contaminants.

Concrete reservoirs are the traditional method used across the island. After experimenting with one himself – a small structure that could hold one week’s water supply – Michael soon realized he would need something substantially larger to meet the demands of their growing Safari Camp, not to mention considerably more eco-friendly than concrete. After experimenting with the locally-available plastic used to line garden ponds and greenhouse mesh as a cover, he realized these materials weren’t going to work either. The plastic was weak and unlikely to last long, and the mesh did little to prevent insects and other contaminants from entering.

What is rainwater harvesting?

Rainwater harvesting involves capturing and storing rainwater for later use. When implemented and maintained correctly, rainwater harvesting can be a sustainable practice, reducing demand for freshwater from traditional sources, such as groundwater or surface water. It can also help prevent erosion, flooding, and water pollution.

Finding reservoir inspiration in unexpected places

The challenge was finding both a sustainable and affordable water collection solution.

Michael got his lightbulb moment from Pronaca, one of Ecuador’s largest suppliers of chicken and animal protein. He saw how their sewage plants used large plastic ponds, lined with geomembranes, to generate methane gas from their animal waste. These ponds were fully sealed, thereby preventing any gas from escaping as well as any contaminants from entering. He wondered if the same system could be used to collect and protect the rainwater at their camp.

Around the same time, friends of theirs and fellow hotel owners, Luca and Antonella, were facing similar challenges, some 14,000 km along the equator in Campi Ya Kanzi, a boutique eco-lodge in southern Kenya. Their water collection and storage solution took the shape of PVC ‘bladders’. In the spirit of innovation, Michael and Luca would bounce ideas off each other as they both experimented with various systems, some more successful than others.

Rainwater Harvesting: A first of its kind in the Galapagos

The rainwater reservoir at Galapagos Safari Camp

The final system at Galapagos Safari Camp took inspiration from both sources and was a first of its kind on the islands. A geomembrane-lined reservoir measuring 36m long, 32m wide and 8m deep, with a storage capacity of 9,216,000 liters of water.

The permanent buildings in the camp, namely the Main Safari Lodge and the Family Suite (i.e., not the tents) are fitted with drainage pipes that feed the rainwater directly into the covered reservoir. This freshwater is then channelled through a sophisticated ultraviolet treatment process that uses a series of carbon filters. The water is tested every three months (samples are sent to a laboratory on the mainland). To date, the results have never shown any traces of contamination.

While visible from the air, our rainwater reservoir is surrounded on all sides by trees and cannot be seen from the camp itself.

This treated water is the camp’s primary source of drinking water and is used in our kitchen, at our water bottle fitting stations, and at all our drinking water touchpoints, including the jugs of water in the tents.

To increase the surface area for rainwater collection, Michael spread out the leftover geomembrane on top of a nearby hill. The rainwater collected here is first passed through a natural filtration system of lava rock before entering the main reservoir, and then the second treatment process.

The Gray Water

The ‘grey water’ sits on top of the sealed reservoir and attracts many birds. The water is also used as a second source of water for the camp (eg. in toilets, irrigation)

A second source of water that collects on top of the covered reservoir is also put to good use. This ‘gray water’ is siphoned off and used for the camps’ toilets, showers, wash basins, and laundry facilities. It also irrigates the kitchen garden.

The gray water also creates a wildlife-friendly humid zone for numerous bird species including our resident finches, mockingbirds, flycatchers and white-cheeked pintail ducks, as well as for coastal birds such as frigates which have been seen here washing out the salt from their feathers.

A stone wall surrounding the reservoir prevents tortoises from falling into the gray water.

The Facts

Building the reservoir, back in the early days of the camp

- The reservoir holds 9,216,000 liters of water

- The camp uses approximately 30,000 liters of water per day

- The reservoir can meet the camp’s water needs for 307 days of the year. (Given that the camp is not occupied every day of the year, we estimate the reservoir to have an overall sustainability rate of around 90%).

- 1 truck containing 10,000 liters of water costs $45

- The reservoir provides an equivalent of 921 trucks of water. That’s a saving of $41,445 a year, not to mention the costs in carbon emissions that 921 trucks would otherwise generate.

- The reservoir cost $20,000 to install, and the investment was recovered within one year.

- The geomembrane has a 10-year guarantee, although it’s expected to last for many years beyond that.

- Other properties on Santa Cruz island have since replicated our model.

“You can’t call yourself an ecotourism operator if you’re pulling water from a community source, and that goes on all the time.” – Edward Norton (when addressing the 2022 World Travel & Tourism Council summit in Saudi Arabia).

More pioneening projects at Galapagos Safari Camp

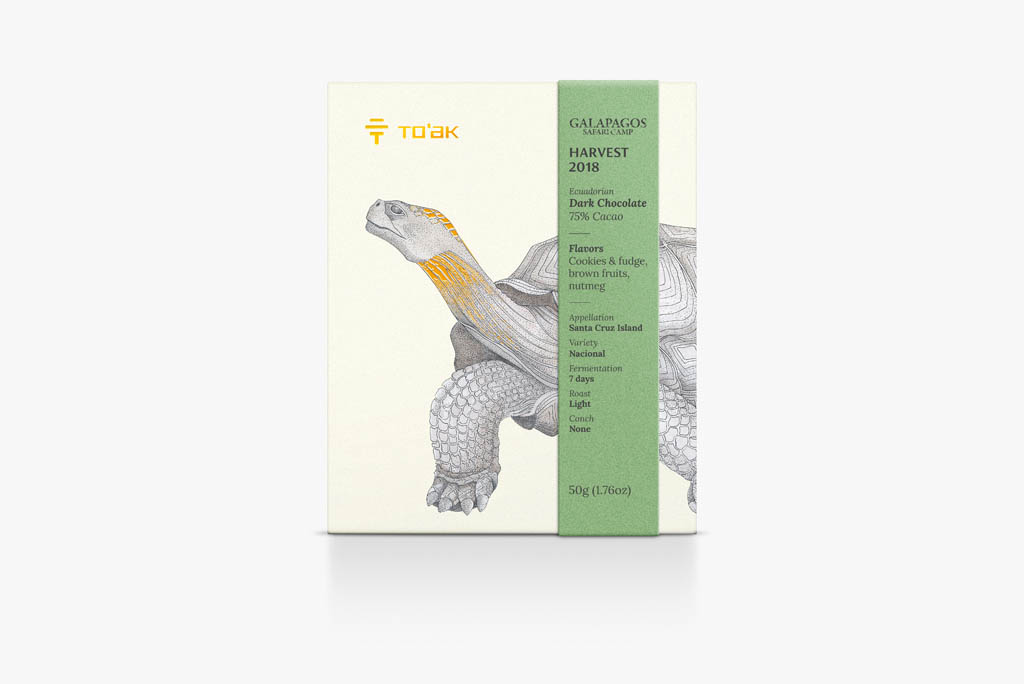

- Discover the story behind the world’s first chocolate bar made with Galapagos cacao. The First Galapagos Chocolate Bar:

- Reforestation and endemic garden projects. Michael and Stephanie worked with the Charles Darwin Research Station to create ‘endemic gardens’. The aim was to demonstrate that endemic gardens could be aesthetically pleasing, thereby encouraging the local population to follow suit, choosing endemic species such as Opuntia echios (Prickly Pear) over introduced / invasive plants such as Lantana camara, the latter being one of the top ten most noxious weeds in the world.

Learn More: Sustainable Hospitality at Galapagos Safari Camp.

Other pioneering rain harvesting projects in the Galapagos Islands

Harvesting water from fog.

We were excited to read about another groundbreaking project in the highlands of Santa Cruz Island that uses large nets to harvest fog and rainwater. Led by Dr Charlie Ferguson, and in partnership with FUNCAVID, this innovative solution has helped to collect over 65,000 liters of water between March and May 2023. This equates to a saving of approximately 0.2 tons of CO2 that would otherwise have been emitted by tankers transporting water to the highlands from Puerto Ayora.